Let Them Call it "Content"

I'm no longer going to be mad about my journalism being called content.

A curious thing happened when I became more active on LinkedIn starting a year ago. As I connected my way around that strange, careerist website, numerous recruiters messaged me to commend me on my “content” and to ask whether I would also like to make some of that sweet, sweet content for them.

Content…like the stuffing inside a seat cushion.

Now, I’m not going to be the guy who writes another diatribe like this one, this one, or this one going off on why many journalists and creatives hate having their work called content. Nor am I, by the way, going to pass judgment on freelancers who turn to branded media gigs in this brutally tough market—as news outlets, Hollywood, arts nonprofits, and publishers all struggle, it’s hard to make a buck out there.

Rather, I was curious why my content suitors had approached me, and was inspired to dig more into what the word really means. I started with Merriam-Webster, which goes real wide with its definition. Content (noun): “the principal substance (such as written matter, illustrations, or music) offered on a website.” But if you continue searching elsewhere online, content is almost always associated with marketing. Under one of Google’s top results for “what is content?”, the writers at JustWords explain: “Through content, individuals discover, take in, and engage with brand information.” Notice the word I bolded.

So what is content? I think it’s actually a useful term both as a frame of reference and a differentiator: it helps separate art/journalism that has at least some plausible independence from commercial aims from creative work whose entire raison d’etre is bolstering a brand or a company or an industry. For instance, textbook journalism is supposed to follow truth no matter where it leads, including holding the powerful accountable. But content is always going to have editorial guardrails—the storytelling or educational information ultimately needs to make a client look good.

Maybe one reason these recruiters approached me is because I can hardly claim to be a content-less purist. If I think through the aims and effects of the many hundreds of articles I’ve written, I have to admit I’ve produced plenty of content-y pieces—even while on staff for newspapers and news magazines. For every hard news story or investigative feature, I still filled quotas as a staffer by churning out some articles that were essentially masqueraded PR pieces in service of an individual or company. I mean, maybe the writing passed on a quick glance as journalism because it had some original reporting or interviews in it. But if I’m being honest, the idea of earned media always felt like a giant favor to whoever I was writing about. It was, for all intents and purposes, content.

What concerns me today is conflation. And it’s not just my thin skin about randos in my inbox associating my best work with content. Here’s the executive editor of Tribune Publishing recently calling all his papers’ stories content. I can also think of a couple instances in newsrooms when I heard fellow journalists or editors, perhaps unthinkingly, refer to our publication’s articles as content—which presumably included pieces of mine and my colleagues that I would not have put in that category. It felt like a cheapening of the investigations or narrative stories we tried to write as actual exposés or pieces of cinematic art.

Perhaps if the word “content” wasn’t so loaded—like that bland Merriam-Webster definition—I wouldn’t have minded. But as content becomes the go-to term for anything published anywhere in the larger media sphere, that’s problematic—especially when you know about content’s history and underlying aims.

Content Creep

Content’s origins have everything to do with marketing. For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, marketing meant interruption. Whether in print, radio, or television, an advertisement usually meant a break in the middle of whatever the audience had come to read, watch, or listen to.

Here’s a (bad) example:

We interrupt this essay to bring you a message from our sponsor: Chris Walker, whose newsletter The Longform Lowdown you should definitely subscribe to below!

As anyone who’s watched Mad Men will appreciate, marketers tried to make those interruptions entertaining—or even, as Don Draper preferred, profound.

This approach to marketing always meant that publishers retained power since it was the publisher’s programming that drew the audience. Marketers therefore had to spend big in order to access and influence those audiences.

But over time, corporations realized there might be a way around this. According to the Content Marketing Institute, which produced a piece of meta-content in the form of a documentary called The Story of Content: Rise of the New Marketing, some of the world’s savviest business minds realized that instead of going to publishers, it might be cheaper to become publishers.

As early as the 1890’s, a few companies began coming up with ways to draw their own audiences. John Deere started producing The Furrow in 1895, a farming magazine. Five years later, a French tire company launched a little pamphlet called the Michelin Guide, which listed hotels throughout France and also, not coincidentally, tire shops and gas stations (the famous Michelin star restaurant ratings were added in 1926). Then, in the 1930’s, Procter & Gamble had the idea of producing its own radio dramas. They became known as soap operas.

The genius behind these branded media properties was subtlety. As a John Deere executive mentions in The Story of Content, even the oldest issues of The Furrow might only mention the company’s name a handful of times. John Deere realized it didn’t need to be heavy-handed; readers would subconsciously think of John Deere tractors and farming equipment as they read the magazine’s educational and entertaining stories about agriculture. This was in clear contrast to the interruption model of advertising, which was more like a cudgel. Think of content marketing like a Trojan Horse; audiences are attracted to branded media because it does have some real informational or entertainment value, even if consumers are being discreetly advertised to. The value of the content—like those soap operas—is worth it to viewers.

Still, throughout most of the 20th century, companies like John Deere and Procter & Gamble were the exceptions, rather than the rule. For one thing, the interruptive model of advertising remained effective, if expensive, and most corporations stuck with it. Being a publisher also comes with its own set of challenges. Great content requires great artists and storytellers, and for decades the best writers and artists could make decent livings at magazines, publishing houses, and art institutions.

Then came the Internet.

Content is King

In 1996, a then-41-year-old Bill Gates wrote an essay that effused about the possibilities of the Internet. Through the essay’s title, he popularized a phrase that’s still used today: “Content is King.”

One of the exciting things about the Internet is that anyone with a PC and a modem can publish whatever content they can create. In a sense, the Internet is the multimedia equivalent of the photocopier. It allows material to be duplicated at low cost, no matter the size of the audience.

Most of this content, Gates predicted, would present as either information or entertainment. And it would be so valuable that people would pay for it…right?

For the Internet to thrive, content providers must be paid for their work. The long-term prospects are good, but I expect a lot of disappointment in the short-term as content companies struggle to make money through advertising or subscriptions. It isn’t working yet, and it may not for some time.

Gates proposed a third solution to pay creators: He believed that an ecosystem of micropayments would develop wherein readers would pay as little as 1 to 5 cents for every webpage they visited—money that would then go directly from readers’ pocketbooks to writers and publishers.

If only things worked out that way!

There were two monsters on the horizon that didn’t appear to be on Gates’ radar in 1996. The first was social media, along with the idea that users would spend way more of their time consuming text, images, and videos created by other users as opposed to traditional publishers. And most importantly: the users would give up this “content” for free.

Within a decade of Gates’ essay, MySpace and Facebook laid the groundwork for what we now know as influencer culture. So began a weird trajectory that, according to a poll I heard cited in an episode of NPR’s Planet Money, has become the active career plan for about 1 in every 4 Gen Zer’s: amass a following by posting some (curated) version of your personal life, then make deals with brands to help companies sell stuff to your followers.

But the far bigger monster Gates didn’t see coming? Google.

As Google search basically became the internet and drove the majority of web traffic, it became important for brands to place as high up as possible in search results to keep customers’ attention on their products and services. So just like social media birthed influencing, Google birthed search engine optimization, or SEO for short.

An entire profession emerged just to figure out how to place higher in Google search results. And these SEO experts realized that the key to helping brands stay relevant in search results was producing an always-on stream of content.

By the end of 2007—by which time Google had established dominance and never looked back—large companies could no longer rely on the tried-and-true interruptive model of advertising alone. They might still pay Madison Avenue advertising companies to make a Super Bowl commercial, but now they also needed a constant flood of online content to stay relevant in Google searches, which meant that—just like John Deere and Procter & Gamble before them—they all needed to become publishers. As a marketing executive with Marriott hotels says in The Story of Content documentary:

I have a presentation that I give called ‘Publish or Perish.’ It’s the idea that if we don’t start publishing we’re not gonna be around or be relevant. It’s the idea that today, as a brand, we’re all really a media company. All brands are media companies.

All brands are media companies.

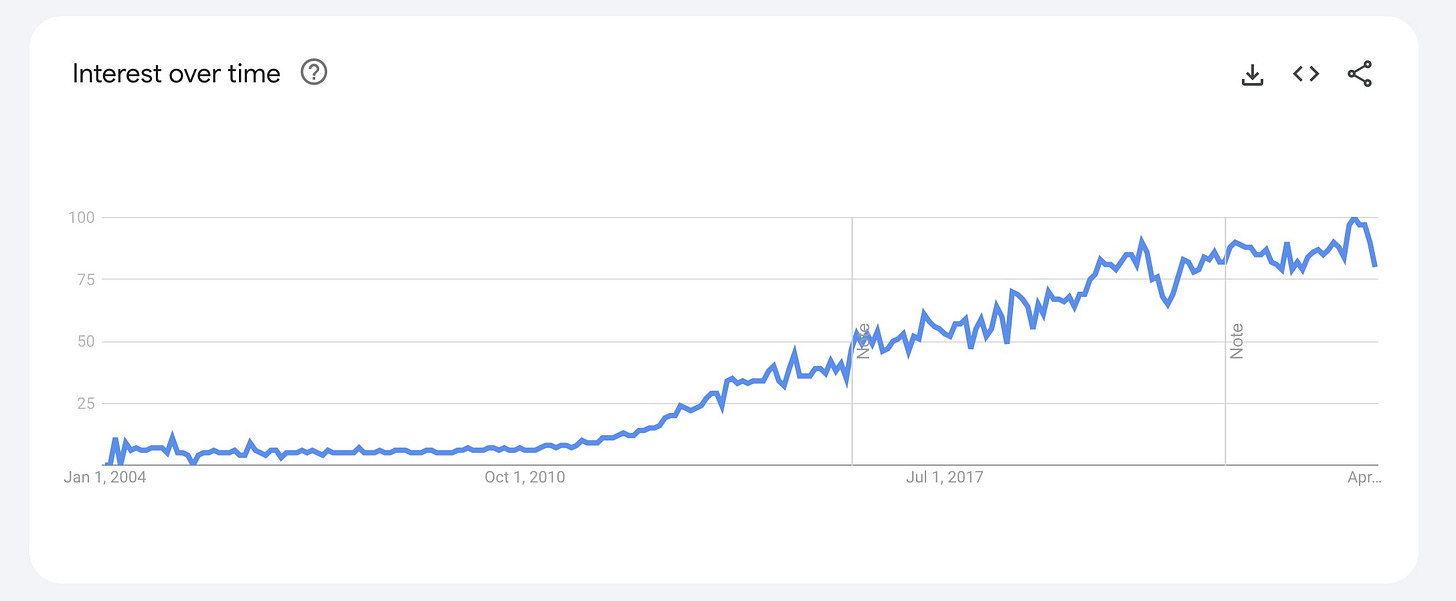

And so it’s not just you or me noticing a surge of content references on LinkedIn and elsewhere around the web. Its rise is directly tied to the ascendance of social media and Google, a trend you can see on the service that made it so ubiquitous. Here’s the Google Trend chart for the term “content marketing” from 2004 to present.

Informed Con(t)ent

Let me say that what makes all of this complicated is that there is some really kickass, objectively creative content out there. Content that I love. The brand that immediately comes to mind is one of the most successful content creators: Red Bull. I could watch their extreme sports videos all day.

The brand brings slick video production to mountain biking, surfing, and even more esoteric stuff like wingsuit jumping that probably wouldn’t exist otherwise. Other brands like The North Face also hire videographers to do the same around sports like alpinism and climbing. It’s good stuff. I’m a fan. It’s probably fun to make, too.

But for every high-budget action video and quasi-journalistic documentary funded by corporations (who are still trying achieve market dominance and get you to buy things), don’t we want more art and writing that isn’t hyper commodified? Don’t we want to be on social media without being influenced to all the time?

That’s one thing I’ve found refreshing about Substack so far: a lack of content, at least in its historic, marketing sense. It helps that writers here can amass their own email lists and earn money through subscriptions. But as this platform explodes and ever more writers come on board hoping to survive off their art, I fear readers will soon feel subscription fatigue—if they haven’t got there already. If subscriptions drop off because there isn’t enough money to go around, won’t creators begin to feel the same temptations to commodify their work through brand partnerships?

We’re in for rough times ahead. I don’t have stats for other fields of creative work, but the journalism industry I’ve spent my career in is in absolute freefall. Things are likely to get worse if Google continues to roll out AI summaries of news articles. So much for all that SEO work that news websites have been doing.

Even if creating content is, by its definition, selling out, we’re at a dark place where many creatives feel pressured to participate. It’s Hollywood writers working on Marvel movies they don’t want to because no one is buying their original scripts, and freelance journalists who want to just report the news spending half their working hours telling corporate clients, “let me tell your brand’s story.” In all likelihood, as I go back into freelancing myself, I will end up in situations where I take take on a content gig or two (or three or four).

But here’s where researching content’s history helps: I won’t kid myself about what I’m doing.

And the next time an editor or one of those LinkedIn recruiters calls my best journalism “content?” Well, it could just be a naive comment. But it could also signify an attitude about what they really want: a priority on clicks, and some search-engine-optimized work that’s just entertaining or informative enough. If you ask me, that’s good to know upfront. I’d like to know who I’m dealing with.

Let them call it content.

what a world could have been with micropayments and creator<->consumer support. i mean i see patreon (or even onlyfans) as something akin to it which is lovely? but also drowned out by the noise brought about by google/facebook/etc platforms which have brought about so much noise to what used to be such a cozy, weird lil cyberspace.

very interesting take, Chris. Thanks for sending